Image by Pete Linforth

Article Summary: This article explores the importance of understanding family ancestry stories and how DNA testing can uncover the true origins of one's heritage. The author shares personal experiences of discovering inaccuracies in her own family story and the emotional journey of connecting with her roots. The article emphasizes the cultural significance of accurate ancestry and the respectful approach to understanding one's genetic background.

Family Ancestry Stories: Myths vs. DNA Facts

by Cairelle Crow.

What’s your family story? This is the first question I ask every client. Before creating a plan to engage in DNA testing and research, I always assess the knowledge of the individual regarding their family history as they know it. The story of a family’s origin is usually passed down through generations but much like the old game of Telephone there are nuances lost in the translation, assumptions are made, and it’s often the case that the reality of a family’s roots doesn’t always match the story.

I am a prime example of someone who has lived with a family story that was woefully incorrect. I was raised in New Orleans with unfettered access to my mother’s family and its stories of our roots, but did not have a regular connection with my father or his side of my family. As a result, I grew up with little knowledge of my father’s family, but with a strong sense of cultural belonging in the Southeast Louisiana region in which many of my maternal ancestral lines have lived since their arrival in 1721.

Family stories passed down by my maternal grandmother, the “old aunts” (her sisters), older cousins, and other extended family, led me to believe I was mostly French and Acadian, with a smattering of Scots Irish and English, and directly descended from President Zachary Taylor. What little I did know about my father’s side of my family came from my grandmother. She said he had some German ancestry and may have been a descendant of the Blackfoot Confederacy. I had long, straight, dark hair, brown skin when I tanned, and dark eyes, so everyone thought that was right.

I didn’t identify culturally as Native American, but neither did I question any of this ancestral story for many years. I still have no idea of its origin. From where exactly did my grandmother hear that my father was a descendant of the Blackfoot Confederacy? She is gone now, and I’ve asked my mother, but she doesn’t remember.

After the advent of direct-to-consumer DNA testing, I did my own testing and began a deep re-exploration into all the branches of my tree. I suspected there were some inaccuracies in my family’s stories about our deeper origins. I also DNA-tested various family members. Eventually I uncovered family secrets that blew part of my family story into a million pieces and caused a lot of heartache.

Some people, whether because of adoption or another circumstance that has removed them from the knowledge of their own genealogical family tree, may have no story at all. My husband grew up with zero knowledge of his genealogical family of origin because he was placed for adoption at birth.

The first time he met a person who was genetically related to him was at the birth of our oldest daughter. His family story, and his sense of identity, came from the family into which he was adopted. His adoptive father’s side is French, his adoptive mother’s side is mostly English, Irish, and Scottish, a blend that seems to occur frequently in those with Appalachian roots. Through DNA testing, we eventually discovered his recent genetic roots lay in the northern part of the United States, in Chicago, but he feels no pull to that part of the country or its culture.

His cultural sense of self was forged in and around New Orleans and he is very much a part of its fabric, despite having no close genealogical connections in southeastern Louisiana. He and other adoptees, along with those who grew up away from their family of birth, are examples of the very powerful magic that lies within the family of influence.

Expulsion from the Family

Expulsion from the genealogical family is one of many scenarios that occur that keep people from the verbal retelling of family history, and it prevents them from asking questions, looking at pictures, participating in family traditions, and occasionally, feeling a part of the culture. One of the beauties of DNA testing is the reconnection it provides to our heritage. This is vitally important to the people who, for whatever reason, have been removed from the source that would give them information about their heritage, their roots, their own family story.

Regarding inaccurate family stories, the most common one I come across in the United States, and the one that is most strongly defended, is the assertion that an ancestor—a great-grandparent, or a great-great-grandparent—was “full-blooded Native American,” usually Cherokee. As I mentioned, my own story also had a Native American ancestor on my father’s side and I’m nearly 100 percent sure that is incorrect, at least on his side of my genetics.

I did have one experience that has kept me from fully committing to my lack of Native American ancestry. Back in the early 2000s, I worked as a travel nurse. One assignment took me to the Southwest, where I stayed for many weeks. I worked in the ICU, and there was a Navajo elder and healer on staff who rounded daily on each patient that was a member of the local tribe. Hers was important work that made a big difference in how families coped with critical illness, and how patients recovered from it.

On a day when I was caring for one of her patients, she approached me to discuss the patient, and the conversation ultimately turned to the spiritual, as it often does between magical people. During our talk, she mentioned to me that I have “Native blood.” At the time, my hair was very long, and near to black and when I worked, I kept it pulled back in a long braid. I shared with her that my appearance sometimes led people to think that I was Native American, but that I really wasn’t. She laughed and said, “But you are Native.” I asked her how she knew that, and she replied, “I know you have Native blood in you because I see your ancestors standing behind you, and they are telling me so.”

Her talk with me, which I keep within my heart and mind as valuable words of wisdom from a Navajo elder and wise woman, does still give me pause for reflection. The other, private, things she told me have indeed come to pass. I also have lines on my mother’s side that are “brick walls,” meaning I can’t get past a certain ancestor. They’re relatively recent—great-great-grandparents— and they are from the area of Louisiana in which there is often found among the people a mix of French, Native American, and African heritage. I do have a tiny, and consistent, portion of my ethnicity result that is from Africa, and I also have French in my ethnicity result, so perhaps I descend from an ancestor who carried that particular mix of DNA and I just haven’t inherited the Native American part of it? However, that’s a stretch with no evidence, and I don’t know that I will ever know for sure.

I do know that I am not culturally Native American, and I consciously mind my words and actions so that I don’t appropriate spiritual practices, dress, or anything else that is considered Native American. However, because of her words, I keep a small bit of earth on my altar to represent, and pay respects to, Native American ancestors that just might be within my energetic DNA.

It is important to remember that a lack of a particular ethnicity in our results doesn’t necessarily mean we don’t descend from certain people. We also need to keep in mind that having a positive ethnicity result doesn’t entitle us to claim that culture and its particulars as our own. Ethnicity estimates are just that: estimates. The science is getting better, but it’s still new.

Ethnicity results are deemed accurate only at a continental level. They do not ever give us permission to appropriate a culture that isn’t the one in which we were raised or trained. I also have Welsh DNA, a fair bit of it, but I am not Welsh. I am American with Welsh ancestry. I have a small and consistent percentage of African ethnicity but this does not mean I can appropriate spiritual or other practices that are associated with African culture. We should always be mindful of these distinctions.

The Lack of Connection to the Land

For Americans, the lack of connection to the land on which many of us live as descendants of settlers and colonizers causes real emotional pain and contributes to the insistence by many people that they’re genetically connected to the Indigenous Americas. I have a theory about why this happens: descendants of settlers and colonizers have no sense of spiritual connection with this land. Our deepest ancestry stories unfolded in lands that are thousands of miles away.

When our ancestors emigrated from their homelands to the United States, we lost that connection to the lands of our own people because they left behind their lands, their dead, their culture. Much was brought with them, but it got lost or was blended into customs and cultures from other lands. As a result, we lost connection to the culture, we lost the overall sense of belonging to the larger stream of consciousness that flows forth from the land into its people. For some, this feeling of loss leads them to seek out a genetic connection to America’s indigenous peoples and when that doesn’t manifest, they are forced to really tune in to the loss.

There are ways to manage this that don’t encroach on appropriation. Connecting via DNA testing to the genetic heritage we each have is a first step. Learning more about genetic family and our roots through traditional genealogy is another because it ultimately leads us to seek out the places from which our own people traveled.

When I first discovered that I have a deep well of ancestral ties to Italy, my intense curiosity about Italian witchcraft made more sense to me. I am what is commonly referred to as an American mutt which is a bit of slang to indicate that I have ancestry from many places. My research does reflect this to be so, and so far I can trace ancestors to England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, France, Germany, Poland, and Italy. I too have felt feelings of disconnection from the land on which I was raised, and this feeling is not uncommon as it has also been shared with me by many others who are also descended from ancestors who traveled.

One way that I manage these feelings is through travel of my own, and I am privileged to be able to do so. I call myself a “tree traveler” as most of my journeys are planned in places to which I have traced an ancestral line. The feeling of standing upon the ground on which an ancestor walked in years gone by is amazing, and it brings that feeling of connection to the fore.

I enjoy wandering cemeteries and graveyards in those places and paying my respects to the people of that place. I support the culture of the place by spending my money on local lodging, food, and crafts made by local hands. I try to respectfully nab a tiny bit of the earth in the form of dirt, a small pebble, or a fallen leaf, so that I can place it upon my altar when I return home. This allows me to keep my feeling of connection and reminds me that I always carry that place within me. The blood and the bones remember.

Copyright 2023. All Rights Reserved.

Adapted with permission of the author/publisher.

Article Conclusion: Understanding our family ancestry stories through DNA testing provides a profound connection to our roots. This journey can uncover inaccuracies and reveal the true origins of our heritage. Embracing these discoveries allows us to honor our ancestors and appreciate the diverse cultural tapestry that forms our identity. Through respectful exploration and acknowledgment of our genetic heritage, we can build a deeper connection to our past and our ancestors and a clearer understanding of who we are today.

Article Source:

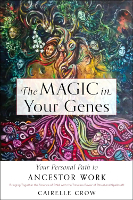

BOOK: The Magic in Your Genes

The Magic in Your Genes: Your Personal Path to Ancestor Work

by Cairelle Crow.

The Magic in Your Genes is geared to those with a known recent genealogical history (parents, grandparents) but is also appropriate for those who are adopted or who have other situations, such as a misattributed parentage event. Combines traditional genealogy with magical practices in a unique guide to deepen your relationship with ancestors.

The Magic in Your Genes is geared to those with a known recent genealogical history (parents, grandparents) but is also appropriate for those who are adopted or who have other situations, such as a misattributed parentage event. Combines traditional genealogy with magical practices in a unique guide to deepen your relationship with ancestors.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as an Audio CD, an Audible Audiobook, and a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Cairelle Crow has walked a goddess path for more than 30 years, exploring, learning, and growing. She has been involved in genealogical pursuits since the late 1990s and began to actively work with genetic genealogy in 2013. She is the owner of Sacred Roots, which is dedicated to connecting people to their ancestral heritage and legacy, and she lectures locally, nationally, and internationally on the blending of genealogy with magic. She teaches the 13-month Priestess of Sacred Roots genealogy magic course and is also an integrative RN and midlife women's advocate.

More books by this Author.