Image by Gallant890 from Pixabay

In this Article:

- What it is like to be a dog in our world.

- Myths and misconceptions about dog behavior.

- How can we understand the unique personalities and preferences of dogs?

What’s It Like to Be a Dog in Our World?

by Marc Bekoff.

Hardly a day goes by that someone doesn’t ask me a “dog” question. I find myself saying over and over again something like, “Did you know that dogs do this or that?” Many people are eager to learn more about dogs — about their different personalities and why they do what they do and how the behavior of dogs relates to wolves and other wild relatives such as coyotes.

When people ask me questions I can’t answer, or for which there aren’t any simple, definitive answers, I tell them honestly, “I don’t know.” In fact, the more I learn, the more I realize all that we still don’t know about dogs, and that isn’t a bad thing. It truly reflects how much we’re learning, how we need to look at dogs as individuals, and how much we need to appreciate that every dog-human relationship is unique. I honestly get upset when people make categorical pronouncements about dogs — saying they can’t or don’t do this or that — and characterize dog-human relationships in a narrow human-centered way.

Dogs Are Always Learning from Humans

However, my deeper hope is that increased understanding will foster more caring. A dog’s feelings matter to them, and they should also matter to us. We should take the perspective and emotions of dogs into account in every aspect of our shared lives. This applies to training.

I prefer to think of training as teaching and educating dogs about how to live in our human-oriented world — which should be done using only positive, force-free methods. But in reality, dogs are always learning from humans.

We often place unrealistic social expectations on dogs, especially homed dogs, who are constantly being asked to do what we want them to do. So giving dogs some extra tender loving care is really good for them and for us.

You can’t “spoil” a dog, nor are there really many “bad dogs.” Most of the time, when dogs “misbehave,” they’re simply doing whatever they have to do to be dogs. Training is a form of education; it’s not a way to program dogs so they always please us.

What’s It Like to be a Dog?

There’s no shortage of dogs who will benefit from humans trying to figure out what it is like to be a dog. As I’m writing this book, dogs can be found in around 64 million American households — which accounts for 53 percent of all US homes. In Japan, dog companionship is very widespread, and people like to travel with their dogs, so much so that Japan’s Shinkansen bullet trains are creating a pet-friendly carriage in which dogs can roam free and relax as they travel with their people.

Dogs themselves are a very diverse species — Canis lupus familiaris is the most diverse mammal. As such, there is no “universal dog.”

Further, laboratory studies that seek to assess dog behavior and human-dog relationships can provide limited or even skewed results. Many times, the dogs used in studies are captive, highly controlled individuals in restricted settings, and just because those dogs don’t do something in a lab doesn’t mean other dogs can’t, don’t, or won’t exhibit that behavior when they’re free. This makes it impossible to declare that “all dogs” do this or that in any particular situation.

Overall, dog breeds don’t have distinct personalities, but individual dogs do — so don’t judge a dog by their cover. Not every member of a given breed will always perform the way people expect.

Likewise, comparative research on dogs and wolves doesn’t allow us to make reliable species-wide conclusions about the cognitive skills of dogs compared with wolves. A lot of research hangs on which tests are used, how they’re conducted, and how individuals are raised.

Free-Ranging, Feral Dogs

In total, there are about a billion dogs in the world, but many people don’t realize that only around 20 percent of those dogs are “homed” individuals — those cared for by people, who (hopefully) provide their dogs with a predictable place to sleep, healthy food, a lot of love and respect, and veterinary care. This means that roughly 750 million dogs are free-ranging or feral and have different amounts of contact, both direct and indirect, with humans.

The good news is that globally there are numerous projects concerned with the humane care of these individuals. Of course, some dogs do indeed need us, but many feral dogs can do quite well on their own. What might happen with dogs if humans weren’t around is what Jessica Pierce and I explore in our book A Dog’s World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World without Humans.

Homed Dogs Lose Freedoms

Homed dogs also lose countless freedoms, meaning they can’t always be who they really are. We’re constantly telling dogs what they should or shouldn’t do as we helicopter parent their dogness out of them. Too much fussing and pampering of family dogs can actually compromise their well-being.

In The Book Your Dog Wishes You Would Read, British dog trainer Louise Glazebrook puts it succinctly: “I actually got really emotional, because I saw in lockdown what we as a society were doing to dogs. I remember sitting there one night just crying — we call ourselves a nation of dog lovers, yet essentially, we’re [screwing] them over. It felt like this really horrible moment for dogs.”

Along these lines, in her book Love Is All You Need, Jennifer Arnold notes that dogs live in an environment that “makes it impossible for them to alleviate their own stress and anxiety.” According to Arnold, “In modern society, there is no way for our dogs to keep themselves safe, and thus we are unable to afford them the freedom to meet their own needs. Instead, they must depend on our benevolence for survival.”

Some people even wonder whether we deserve dogs. I frequently ask people to cut their dog some slack when possible because, in our humancentric world, what a dog wants and needs doesn’t always mesh with what humans want and need. I often wonder if the process of domestication — which David Nibert has dubbed “domesecration” — might cause “collective trauma” in nonhuman animals. While we usually only consider collective trauma to be something that impacts humans, there’s no reason to think it might not apply to nonhumans.

Good Dog! Bad Dog!

Often when we tell a dog they’re a “good dog” — and most people don’t say this enough — we’re letting them know that they did something we like, not necessarily something that is an expression of being a card-carrying dog who expresses “good dogness.”

Conversely, when a dog does something that comes naturally — that expresses their dogness — we typically tell them they’re being a “bad dog.” This causes problems in individuals, and it impacts the species, since it means we are continuing to select for traits that we find appealing, but which might be highly detrimental to what makes a good life for a dog.

For example, I often hear that there’s something wrong if a dog doesn’t like to play, doesn’t eat a meal, doesn’t want to go to the dog park, needs alone time, or just seems to be having a bad day. Normalizing certain dog behavior as universal, or being overly simplistic about the reasons why dogs do certain things, is misleading and can cause huge problems.

Of course, it is important to note changes in behavior, disposition, or mood, but like us, canines can have good days and bad days, ups and downs. Dogs are not always up and there for us, and that is a normal part of being a dog.

In fact, some of this misguided care is related to the many misleading myths about who dogs supposedly are and what they should do. For instance, dogs are not our “best friends,” and they don’t love all humans unconditionally. When dogs love, it’s more than mere attachment — it’s real love.

If your dog doesn’t seem to love you, there’s not something “wrong” with the dog; dogs are not unconditional lovers, as they’re often touted to be. Dogs have minds and feelings of their own, and they’re pretty choosy. Their close association with humans might be because they possess a gene that lowers their stress, so they’re more relaxed around people, but that doesn’t mean they’ll love you regardless of how you treat them.

Dogs Have Preferences and Personalities

While dogs can and do love people, and often display remarkable devotion, any given dog is not always going to be in the mood to cuddle or play at any given moment. Dogs have different preferences and personalities.

In his award-winning book The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts, Gary Chapman identified five different aspects of human-human relationships that are important for keeping a relationship fresh and growing: acts of service, gift-giving, physical touch, quality time, and words of affirmation. How they apply to dog-human relationships is interesting to ponder.

My take is that it all depends on context — who the dog is, who the human is, the nature of their ongoing relationship, and what’s happening at the moment for each of them, just like in any human-human relationship. All five are an integral part of the language-of-love package, and they’re difficult to separate. All are essential and important for staying in love and keeping a relationship fresh and growing amid the demands, conflicts, and boredom of everyday life.

In other words, to understand your dog’s behavior, you always have to consider the context for your dog. That means paying close attention to who the dog is, who you are, and the nature of your unique relationship. That’s why there are so many mysteries and too many myths floating around.

Each dog and every dog-human relationship is unique. We can’t assume there are quick, simple, cut-and-dried answers to all our questions about what makes dogs tick.

Copyright 2023. All Rights Reserved.

Adapted with permission of the publisher,

New World Library — www.newworldlibrary.com.

Article Source:

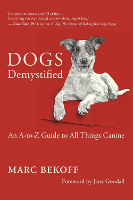

BOOK: Dogs Demystified

Dogs Demystified: An A-Z Guide to All Things Canine

by Marc Bekoff.

Dr. Marc Bekoff is an expert at turning cutting-edge science into practical, reader-friendly information. The encyclopedic entries in this book cover everything related to dog care, dog-human relationships, and dog behavior, cognition, and emotions, making this the accessible book that every dog lover should have.

Dr. Marc Bekoff is an expert at turning cutting-edge science into practical, reader-friendly information. The encyclopedic entries in this book cover everything related to dog care, dog-human relationships, and dog behavior, cognition, and emotions, making this the accessible book that every dog lover should have.

In concise, readable A-through-Z entries, Marc Bekoff covers it all, from aggression to pack formation to zoomies, and explores why dogs do what they do; exactly how to meet any dog eye-to-eye, nose-to-nose, and ear-to-ear to understand their world better; and how tuning in to a dog’s unique personality leads to happier dogs and happier human companions.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as a Kindle edition, an Audiobook and an Audio CD.

About the Author

Marc Bekoff is the author of Dogs Demystified, as well as thirty-one other books (or forty-one if you count multivolume encyclopedias). He is professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder; has won many awards for his research on animal behavior, animal emotions (cognitive ethology), compassionate conservation, and animal protection; has worked closely with Jane Goodall; and is a former Guggenheim Fellow.

Marc Bekoff is the author of Dogs Demystified, as well as thirty-one other books (or forty-one if you count multivolume encyclopedias). He is professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder; has won many awards for his research on animal behavior, animal emotions (cognitive ethology), compassionate conservation, and animal protection; has worked closely with Jane Goodall; and is a former Guggenheim Fellow.

Visit him online at MarcBekoff.com.

More books by this Author.

Article Recap:

This article explores the complexity of understanding what it’s like to be a dog in our world. Marc Bekoff discusses the importance of recognizing each dog’s unique personality and behavior, as well as the distinctions between homed and free-ranging dogs. The article emphasizes the need to approach dog-human relationships with care, recognizing that each one is unique. Bekoff also challenges common myths about dog behavior and stresses the importance of positive, force-free training methods.